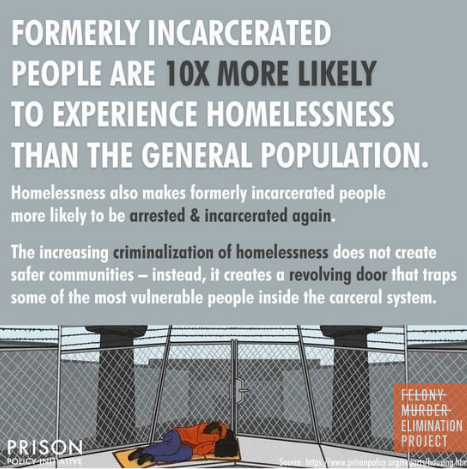

In a vicious cycle termed the homelessness to prison pipeline, formerly incarcerated people are 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general population. Around 50,000 of the people released from jail or prison every year have nowhere to go but the streets or a shelter, a number only exacerbated as more jurisdictions choose to criminalize homelessness, rather than implement policy that works to alleviate homelessness.

The homelessness-to-prison pipeline describes a repeating cycle where homelessness increases the likelihood of incarceration for minor offenses, like sleeping in public, and incarceration makes people far more likely to become homeless due to barriers to housing and jobs, trapping individuals in a revolving door between shelters and jails. This cycle is fueled by policies criminalizing homelessness, the lack of housing support for returning citizens, and underlying issues like poverty and behavioral health needs, creating a costly and harmful system.

In 2024, the United States Supreme Court issued a ruling (City of Grants Pass v. Johnson) that made it easier for jurisdictions to criminalize homelessness. In their 6-3 decision, justices said enforcing a camping ban is not equal to cruel and unusual punishment. The ruling overturned a lower court ruling that kept the ban from being enforced. In response to the ruling, Ann Oliva, CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, said “We are incredibly disappointed and we’re worried about how quickly some communities will move to enact local ordinances that are now legal under this ruling.”

As more communities turn to criminal interventions to address homelessness, some are choosing a more holistic approach to interrupt the jail-to-homelessness pipeline, from financial assistance and supportive housing to predictive screening and wraparound services.

- In Tulsa, Oklahoma, 97% of the people helped by the Center for Housing Solutions, Inc.’s housing navigation team have maintained housing in the first year after exiting jail, and 90% have not had any new criminal charges. The team’s success can be attributed to location and flexible funding. The team is embedded at JusticeLink—the city’s criminal justice diversion hub where people recently released from jail can get help navigating court and government assistance systems. The team also distributes flexible financial assistance to help people pay for upfront housing costs like application fees, security deposits, and risk fees.

- Pima County, Arizona‘s Department of Justice Services opened a transition center where people in county jail for nonviolent misdemeanors can talk to “navigators” to identify barriers they face and services they’ll need when they get out, such as housing, food, medical care, and transportation. The transition center is operated with support from the Housing First Program, and many of the navigators have personal experiences similar to those they are trying to help.

- In Waterville, Maine, the Mid Maine Homeless Shelter and Services operates 11 units, using a Housing First model, for youth leaving jails and other public systems. All 11 units are together to reflect this age group’s unique developmental need to live near peers of the same age. Intensive case management is available 40 hours a week on-site to help youth integrate back into communities, and other mobile wraparound services are available on an “as needed” basis.

To read more about the troubling practice of using the carceral system to address homelessness, you can read “Jailing the homeless: New data shed light on unhoused people in local jails” at the Prison Policy Initiative website. Prison Policy Initiative produces cutting edge research to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization, and then sparks advocacy campaigns to create a more just society.